Big Pharma says lower prices will mean giving up miracle drugs. They are indifferent.

For the first time, the federal government has negotiated directly with pharmaceutical companies on the prices of a few medicines. The new prices, announced in mid-August, will go into effect in January 2026, and will help the Medicare program cap individual patients’ out-of-pocket spending on their prescriptions per year at $2,000.

The historic plan, which has been floating for decades, was opposed for a long time by “Big Pharma” until the Democrats in Congress passed it and President Joe Biden signed the 2022 Tax Cuts Act.

Pharma tried to stop the consultation plan in court after it became law. Their concern – namely, that this “price control” will stifle innovation – has been confirmed by Republicans and policy commentators in the recent price cuts. With low profits, companies like Pfizer and Merck argue, it will be difficult to hire scientists, invest in laboratory space, and create clinical trials to test future medicines.

Sign up here to explore the big, complex problems facing the world and effective ways to solve them. Posted twice a week.

It’s a terrifying proposition: that if we try to control drug prices for the 67 million Medicare patients now, we could prevent the development of future drugs that could save lives. The implication, if not the obvious, is that we are jeopardizing the cure for cancer or Alzheimer’s disease or some other incurable disease.

But we have good reason to believe that the current policy will not have such a trade in the near future. For one, pharma is very lucrative, and these negotiated prices, while they may reduce profit margins, should not reduce the incentive to innovate, according to several key studies of industry. Second, if we are concerned about future innovation, we should focus on making it easier to develop drugs – and this is actually one area where AI shows promise. By identifying the best candidates for potential treatments early in the research process, we can accelerate development and further reduce costs – without losing tomorrow’s success.

We can lower drug prices

The argument against profit cutting often goes like this: Drug companies spend a lot of money making drugs, including some drugs that never make it to market because they don’t work. Once they have a new, effective drug to sell, they need to make more money to cover their development and other costs, so they can take profits and invest. much to research and development for the next generation of medicines.

Most of the other rich countries, such as Australia and the UK, use the central role of the government in their health care system to negotiate lower prices while promoting their medical reform sectors. But in the US, before the IRA provisions became law, prices were largely left to the free market and individual conditions negotiated with manufacturers, private insurers, the government and pharmacy benefit managers. Various rebates, discounts, and other financing methods often confused and increased the prices of drugs for Americans. As a result, the US pays the highest medical costs in the world.

Because of how much we pay, Americans generally get first dibs on new medicine. But that early access is only useful if patients can afford the medicine. Usually, they can’t.

But here’s the thing: This whole thing is wrong. While the Congressional Budget Office reviewed the bill before it passed, its critics said they did not expect a major impact on drug development in the future. The need to cover R&D costs does not necessarily explain, at least not fully, the high cost of prescription drugs in America, according to a 2017 analysis published by Health Issuesjournal of health research.

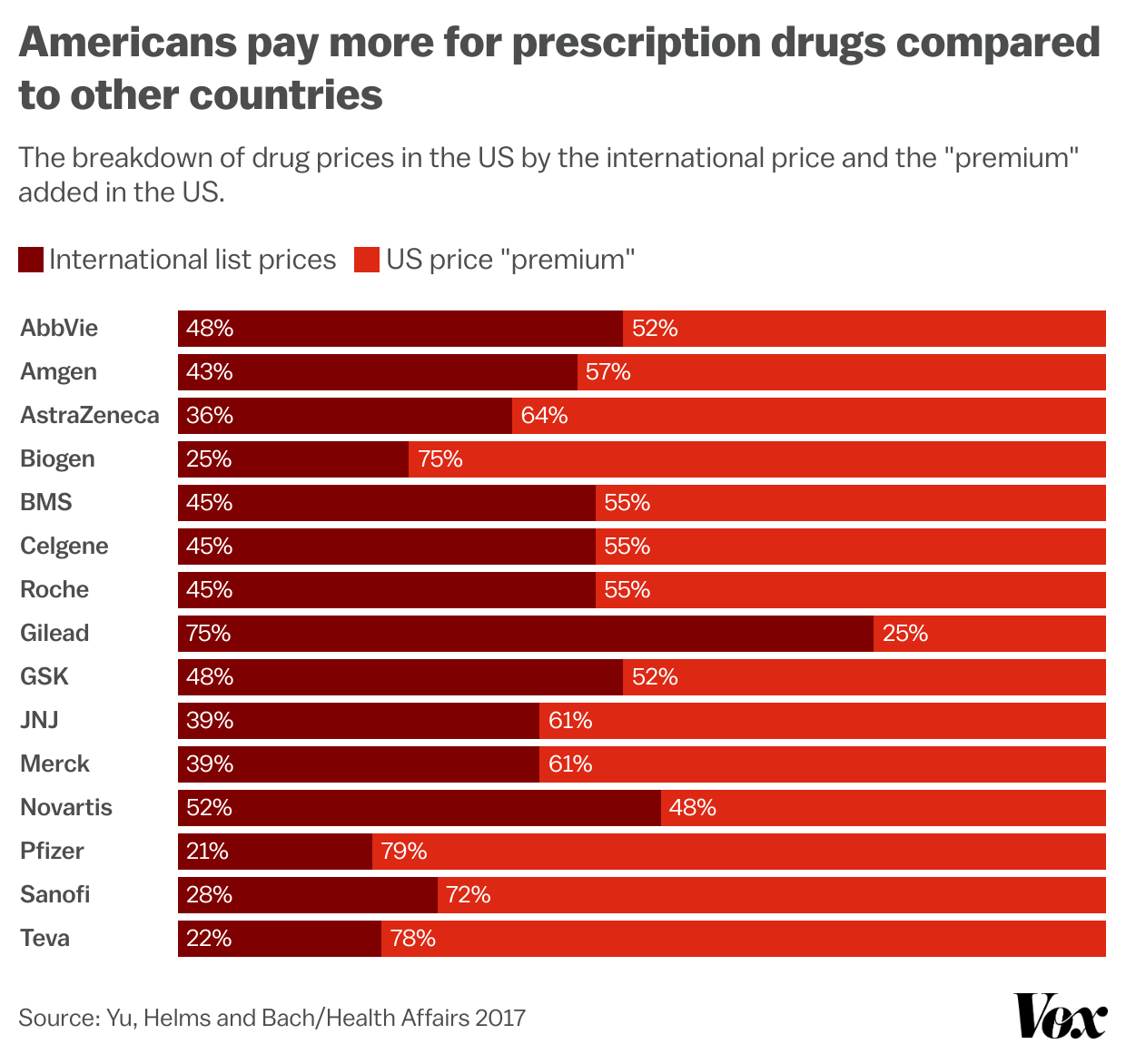

The research – from the Kettering Memorial Cancer Center Nancy Yu, Zachary Helms, and Peter Bach – noted the excessive price paid in the US compared to other wealthy nations. They called this purchase in American R&D “premium.” They calculated how much money the so-called premium generated for the top 15 drug manufacturers in the world and compared it with the spending of different R&D companies.

Dylan Scott/Vox

They concluded that some countries had list prices for drugs that were 41 percent of the prices paid in the US. Big Pharma has reaped as much as $116 billion in one year from these outrageous American prices. In the same year, drug makers spent $76 billion on R&D. These numbers suggest that drug companies may be able to avoid such a charge. “There are billions of dollars left over even after global research budgets are covered,” the authors wrote.

At some point, the prospect of low returns may begin to reduce the industry’s willingness to invest in new drugs and take risky bets with big rewards. But are we close? Regardless of what objection these companies raise, it would be better to examine what they do rather than what they say.

Last year, Richard Frank and Ro Huang at the Brookings Institution looked at the business decisions drugmakers have made since the negotiating provisions became law. The researchers specifically considered mergers and acquisitions, another way big drug companies acquire new drugs (usually by buying promising startups that have already done R&D).

Frank and Huang found little evidence that drug companies expected significant declines in their profits as a result of changes in the bargaining process. If anything, they found more drug interactions in the early and late stages. Total M&A spending was not significantly changed and some recent earnings reports have shown optimism for the future.

This makes sense: the IRA has said that Medicare’s negotiating authority has been limited and gradually stepped in. In the first year, Medicare was allowed to select 10 drugs for consultation. Next year, the program could add 15 more and another 15 after that.

How to make more drugs quickly

We have good reason to think that we can afford lower prices for many drugs. But still, it would be nice if we could make the drugs faster, and therefore cheaper. That would naturally lower prices while getting new medicines to people in need. Win-win.

There may be ways to simplify the approval process and approval criteria for many drugs. Author Matt Yglesias outlined some options for Congress and the FDA to consider in his paper, including accepting data from clinical trials conducted in other countries (where trials can be conducted at a lower cost). .

But science is the most formidable obstacle to new drugs. It can take years for researchers to figure out how diseases work, their biological basis, and in doing so consider potential candidates for intervention. From basic research that uncovers those structures to clinical trials that secure FDA approval can take decades. The FDA only issues data when you’ve found something that actually works. This is why the big drug companies spend so much money on acquisitions; even with all their resources, there is no guarantee that in-house scientists will find a promising treatment candidate before an outside researcher does.

The best way to maximize our R&D resources, to get the most bang for our buck when developing expensive human trials, is to identify the most promising candidates early on. But we are dealing with a huge amount of information: the genetic library that each person carries. This is why drug makers are turning to AI for help in programming.

Leading antibiotic resistance researchers have trained computers to hunt everywhere, even the DNA of extinct animals, for molecules that may hold promise in treating the now-hard-to-treat bacteria. cure them. Longevity advocates place the same faith in artificial intelligence. New startups, such as Recursion Pharmaceuticals, described by STAT, have built their entire business around using AI to find potential drug candidates, including those sitting on Big Pharma’s shelves that can be sold to new agents. .

Whether those AI ambitions will pay off is unknown. But they provide another reason for hope.

Oftentimes, drug pricing discussions are framed as either/or. Either lower prices or new treatments, but not both. It is a false choice.

#Big #Pharma #prices #giving #miracle #drugs #indifferent